Dry Oak - Heath Forest

System: Terrestrial

Subsystem: Forest

PA Ecological Group(s):

Central Appalachian – Northeast Oak Forest & Woodland

Global Rank:G5

![]() rank interpretation

rank interpretation

State Rank: S5

General Description

Dry Oak – Heath Forests are large-patch to matrix-sized forests occurring on xeric to moderately dry, acidic sites, often on shallow or sandy soils and/or steep slopes.

Forest overstories range from closed to open and are dominated by oak species (Quercus spp.). Chestnut oak (Q. montana) is most frequent, however, the mix of

oak species varies regionally with red oak (Q. rubra) sometimes the dominant species in the northern counties of Pennsylvania, and the southern and central

counties often features a mix of black oak (Q. velutina), scarlet oak (Q. coccinea), and white oak (Q. alba). Other tree species include sassafras

(Sassafras albidum), blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), sweet birch (Betula lenta), and red maple (Acer rubrum). Hickories (Carya spp.) may be present but

are uncommon. Conifers such as pitch pine (Pinus rigida), Virginia pine (P. virginiana), and eastern white pine (Pinus strobus) are also often among

the list of canopy associates, but do not make up more than 25% of the overstory.

Prior to chestnut blight in the early 20th century, the American chestnut (Castanea dentata) was a major component of forests within much the sites that now support this type.

Stump sprouts are still common in the understory of this forest type across much of the state but seldom reach maturity, most succumb to the fungus before they are mature enough

to produce viable seed.

The shrub layer is dominated by heath species such as mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia), black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata), lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium pallidum),

low sweet blueberry (V. angustifolium), velvet-leaved blueberry (V. myrtilloides), and deerberry (V. stamineum). Other commonly occurring shrubs include maple-leaved viburnum

(Viburnum acerifolium), witch-hazel (Hamamelis virginiana), and sweet-fern (Comptonia peregrina), which can be common under open canopies. Rose-bay (Rhododendron maximum)

can form a dense understory beneath oak canopies adjacent to small streams and seepages in headwater areas. Owing largely to the thick, resistant oak/heath leaf litter

and acidic soils, the herbaceous layer is sparse. Common herbaceous plants include Canada mayflower (Maianthemum canadense), Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica),

pipsissewa (Chimaphila maculata), trailing arbutus (Epigaea repens), teaberry (Gaultheria procumbens), wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis), bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum),

poverty-grass (Danthonia spicata), and pink lady's-slipper (Cypripedium acaule). The groundcover may be very bare, with patches of exposed soil and duff, rock, or leaf litter.

There may be a patchy cover of bryophytes composed of species common to dry, acidic forests such as pincushion moss (Leucobryum glaucum) and haircap moss (Polytrichum spp.).

The Dry Oak – Heath Forest has been widely mapped on Pennsylvania state land. The broadly-defined oak-dominated forest, which closely follows the NVC’s Northeastern and Central Appalachian

oak-pine forest Alliance-level communities (A4393, A4435, USNVC 2019), can be further divided into three sub-types largely representing regional varieties that that follow regionally

specific patterns in soils, elevation, and landform.

Dry Oak – Heath Forests of the Allegheny Plateau and Northeast Oak occur in portions of the High Allegheny Plateau, Western Allegheny Plateau, portions of central Appalachian Mountains,

and southern New England on sandy or rocky soil on dry upper slopes and terraces of sandstone, shale, granite, gneiss, and other acidic parent material.

The canopy is dominated by a mixture of black oak, white oak, red oak, scarlet oak, red maple, and chestnut oak. The low shrub layer is characterized by

ericaceous shrubs such as blueberries and huckleberries. The Dry Oak – Heath Forests of the Central Appalachian Region appear to be intermediates between

dry ridgetop oak forests and richer oak – hickory forests (Dry Oak – Mixed Hardwood Forest) in coves or on sheltered slopes. The canopy of this subtype is

more diverse, and often includes mesic associates such as tuliptree (Liriodendron tulipifera), hickories (Carya spp.), sugar maple (Acer saccharum), and

basswood (Tilia americana). The tall shrub layer mainly consists of witch hazel and striped maple (Acer pensylvanicum); short shrub layer sometimes lacks a

dense cover of ericaceous species. The herbaceous layer is sill sparse, but is more diverse and may include white snakeroot (Ageratina altissima),

false solomon’s-seal (Maianthemum canadense), New York Fern (Thelypteris noveboracensis), and Christmas fern (Polystichum acrostichoides).

The Dry Oak – Heath Forests of the Piedmont and lower elevations in the Central Appalachians is often composed of stunted overstory trees,

dominated by chestnut oak; scarlet and red oak are associates. The tall shrub layer is usually dominated by mountain laurel; with maple-leaved

viburnum, and pinxter-flower (Rhododendron periclymenoides) in the understory. The short shrub layer is well-developed and may be dominated by one

of the common heaths; usually lowbush blueberry. High deer populations have decimated the understory of Dry Oak – Heath Forests of the Piedmont and Central Appalachians.

A recent study of forest regeneration on National Park Service lands in the Eastern Rivers and Mountain Network (Central Appalachians),

part of the NPS Vital Signs project (Perles, S., J. Finley, D. Manning, and M. Marshall 2014, Perles, S., M. Forder, S. Paull, and J. Fry 2017)

suggests that oak forests are in poor condition due to deer overbrowsing.

Rank Justification

The varieties of the Dry Oak – Heath Forest are common, widespread, and abundant in Pennsylvania and in most Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern states. There are hundreds of occurrences of these types in Pennsylvania. Collectively, Dry Oak - Heath Forest accounts for about 38% of mapped forest acreage on lands managed by the PA Bureau of Forestry and the PA Game Commission combined, with occurrences as large as 1,675 acres. There are over 70 plots in the PNHP plots database that represent this type and finer units, assigned to associations described in the NVC. The finer units, which are all represented by dry-site oaks and have understories dominated by heath species, vary in distribution regionally and are influenced by regional significant factors such as elevation, geology, and plant species range. All three finer units are considered Secure (G5) due to their wide distribution and large patch size.

Identification

- Canopy dominated by upland oak species (chestnut oak, red oak, black oak, white oak, scarlet oak); conifer species comprise less than 25% of the canopy; hickories (Carya spp.) are uncommon in the forest canopy

- The canopy may be partially open, but the canopy closure should not fall below 40%

- The shrub layer is dominated by ericaceous (heath) species

- Characteristically sparse herbaceous layer

- Presence of acid-loving species

- Sandy, acidic soils

- Occurrences are found on upper slopes and ridge-tops, often southern exposures

Trees

- Chestnut oak (Quercus montana)

- Black oak (Quercus velutina)

- Swamp white oak (Quercus bicolor)

- Northern red oak (Quercus rubra)

- White oak (Quercus alba)

- Sassafras (Sassafras albidum)

- Blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica)

- Black birch (Betula lenta)

- Red maple (Acer rubrum)

- Pitch pine (Pinus rigida)

- Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana)

- Eastern white pine (Pinus strobus)

Shrubs

- Mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia)

- Black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata)

- Lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium pallidum)

- Low sweet blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium)

- Sour-top blueberry (Vaccinium myrtilloides)

- Deerberry (Vaccinium stamineum)

- Witch-hazel (Hamamelis virginiana)

- Sweet-fern (Comptonia peregrina)

- Low sweet blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium)

Herbs

- Canada mayflower (Maianthemum canadense)

- Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica)

- Fibrous-root sedge (Carex communis)

- Spotted wintergreen (Chimaphila maculata)

- Trailing-arbutus (Epigaea repens)

- Teaberry (Gaultheria procumbens)

- Wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis)

- Northern bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum)

- Bellwort (Uvularia sessilifolia)

- Mountain bellwort (Uvularia pudica)

- Poverty oatgrass (Danthonia spicata)

- Rattlesnake-weed (Hieracium venosum)

- Pink lady's-slipper (Cypripedium acaule)

Bryophytes

* limited to sites with higher soil calcium

Vascular plant nomenclature follows Rhoads and Block (2007). Bryophyte nomenclature follows Crum and Anderson (1981).

International Vegetation Classification Associations:

USNVC Crosswalk:

Northeast Black Oak - White Oak - Pine Forest (A4393)

Central Appalachian Dry Oak / Heath Forest (A4435)

Allegheny Plateau-Northeast Oak Forest (CEGL006018)

Northern White-cedar Wooded Fen (CEGL006507)

Central Appalachian-Northern Piedmont Chestnut Oak Forest (CEGL006299)

NatureServe Ecological Systems:

None

NatureServe Group Level:

Central Appalachian-Northeast Oak Forest & Woodland (G650)

Origin of Concept

Fleming, G., Coulling, P., Neid, S. L., and Fleming, G. 2006. Central Appalachian Dry-Mesic Chestnut Oak - Northern Red Oak Forest (CEGL006057). NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. (Accessed: February 4, 2022).

Neid, S., Fleming, G. P., Largay, E., and Gawler, S. C. 2010. Central Appalachian-Northern Piedmont Chestnut Oak Forest (CEGL006299). NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. (Accessed: February 4, 2022).

Sneddon, L. A. 2015. Allegheny Plateau - Northeast Oak Forest (CEGL006018). NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. (Accessed: February 4, 2022).

Pennsylvania Community Code*

AH : Dry Oak – Heath Forest

*(DCNR 1999, Stone 2006)

Similar Ecological Communities

The Dry Oak – Mixed Hardwood Forest type is similar but occurs on less acidic sites and does not have an overwhelming dominance of heaths in the shrub layer.

Hickories (Carya spp.), are often present in these forest types along with sugar maple (Acer saccharum).

This type may share species and ecological site variables with the state’s mixed conifer – oak forests such as Dry White Pine (Hemlock) – Oak Forest,

Pitch Pine - Mixed Oak Forest, Virginia Pine – Mixed Hardwood Forest, or Red Pine – Mixed Hardwood Forest However, in these communities,

specific conifer species make up over 25% of the canopy and subcanopy of the forest. Pitch pine and red pine are often a sign of past fire.

At higher elevations and ridge-tops, the Dry Oak – Heath Forest may give way to Dry Oak - Rocky Woodland where harsher winter storms,

lower soil moisture, and fertility may result in increased elevation and on southerly exposures.

Fike Crosswalk

Red Oak – Mixed Hardwood Forest

Conservation Value

Oak forests are both economically important and hold significant value for wildlife (Smith 2005, Martin 1961; TNC n.d.).

A number of bird species associated with Dry Oak – Heath forests include the Black-and-white Warbler (Mniotilta varia),

Eastern Towhee (Pipilo erythrophthalmus), Chestnut-sided Warbler (Setophaga pensylvanica), Back-throated blue warbler*

(Setophaga caerulescens), and Eastern wood-pewee (Contopus virens) (Sargent et al. 2017). Open understories, talus slopes,

and rock outcrops within Dry Oak – Heath Forests are often associated with timber rattlesnake* (Crotalus horridus) and

Allegheny woodrat* (Neotoma magister) (PGC-PFBC (Pennsylvania Game Commission and Pennsylvania Fish & Boat Commission) 2015).

*recognized as Species of Greatest Conservation Need in Pennsylvania (Pennsylvania Game Commission and Pennsylvania Fish & Boat Commission 2015).

Threats

Threats to significant occurrences of the Dry Oak – Heath Forest include pests and pathogens, poor forest management, over-browsing from white-tailed deer,

succession due to fire suppression, and fragmentation. Climate change will have profound effects on all ecological communities within Pennsylvania.

The Dry Oak – Heath Forest has been greatly impacted by spongy moth (Lymantria dispar) and the nature of outbreaks

may result in catastrophic loss of forest canopy when combined with other ecological stressors over many successive years of large outbreaks

(McManus et al. 1980). Areas heavily impacted by spongy moth may first appear as woodlands on account of their open canopies and eventually

toward red maple-dominated forests, especially in areas where heavy deer browsing has reduced the abundance of oak seedlings in the shrub and ground layers.

Development of natural gas infrastructure including well pads and pipeline rights-of-way threaten the contiguousness of large unfragmented

patches of this community and reduce the integrity of occurrences.

While invasive plants are uncommon within the interior of large occurrences of this community,

forest edges will often harbor non-native exotic plant species such as multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora),

autumn-olive (Elaeagnus umbellata), and honeysuckle (Lonicera spp.). Invasive plants are often an indicator

of recent anthropogenic disturbance. Changes to natural hydrology and soil chemistry of these forests promotes

invasive plants. Construction of limestone gravel roads and trails and alterations to site hydrology facilitate

establishment of invasive plants such as Japanese stilt-grass (Microstegium vimineum) (Rauschert and Nord 2010, Nord and Mortensen 2010).

Management

Conservation and management efforts should focus on protecting large examples of this community type and ensuring regeneration.

Activities geared towards limiting the spread of invasive plants, controlling deer populations, and promoting natural processes,

like fire, will positively impact this forest community. Limiting fragmentation will ensure habitat requirements are maintained

for forest interior wildlife species requiring large tracts of unbroken forest habitat.

Forestry activities should avoid older-growth stands. Managers should promote extended rotations and uneven-aged management

within large patches of high-quality forests of this type. Lands surrounding rock outcrops and occurring between rock outcrops

should be protected and managed to promote old growth conditions to develop corridors between them, facilitating movement of wildlife species.

Invasive plants found on the edges of Dry Oak – Heath Forest occurrences may find a way into the interior following development of trails,

roads, and rights-of-way. Invasive plant control efforts should be focused on these fragmenting features and along forest edges.

Drainage ditches and road culverts may alter natural site hydrology. Changes to natural hydrology and soil chemistry of these

forests promotes invasive plants. Development of limestone gravel roads and trails and alterations to site hydrology my facilitate

establishment of invasive plants such as Japanese stilt-grass (Microstegium vimineum) (Rauschert and Nord 2010, Nord and Mortensen 2010).

Prescribed fire is a commonly applied managed practice in oak forests, especially Dry Oak – Heath Forests and Dry Oak – Mixed Hardwood Forests.

Fire can be used responsibly as a tool for wildlife habitat management and forest management, and pre-and post-burn monitoring will help better understand forest community response to fire.

Over-browsing by high densities of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) can have a profound influence on regeneration of Dry Oak – Heath Forests.

Shifts toward less-palatable species, such as red maple and sweet birch due to over-browsing, have been documented (reference).

Therefore, control of white-tailed deer is recommended as an important component of management in Dry Oak – Heath Forests.

Research Needs

Because communities are often the basic unit of mapping on public lands and are utilized in predictions for rare species in Pennsylvania under different

climate change scenarios, maintaining accurate, up-to-date maps of plant communities is important for conservation of rare species.

There is considerable variation among occurrences of the Dry Oak – Heath Forest with respect to canopy closure and the density of the understory shrub layer.

Most Dry Oak – Heath Forest patches mapped on lands managed by the PA Bureau of Forestry and PA Game Commission are a mosaic of closed canopy forests

and more open woodland area resulting from variation in edaphic variables and severity of past logging and disturbance events. More should be done to

more precisely map these areas based on local variation in canopy and shrub density as this may impact the value to wildlife species, especially species

relying on interior forest conditions. Mapping the three subtypes and identifying the ecologically similar Dry Oak – Heath Woodland may help in wildlife management on state land.

This type is known from most regions of Pennsylvania. However, PNHP has quantitative data from only a very small number of sites in the Western Allegheny Plateau

and High Allegheny plateau ecoregions, where it is represented by the finer natural communities associated with this region (CEGL006018). Much of the work documenting

matrix-forming communities like the Dry Oak – Heath Forest comes from National Park Service Vegetation Mapping efforts

(Podniesinski et al. 2005, Perles et al. 2006b, 2006c, 2006d, 2006a, 2007b, 2007a, 2008).

More field work should be conducted to document this community in the under-surveyed counties within this region.

Trends

Dry Oak – Heath Forests replaced forests more heavily dominated by American chestnut prior to the loss of this species due to the chestnut blight fungus (Cryphonectria parasitica)

early in the twentieth century (Diller 1965). The number and size of occurrences has declined due to development and logging.

Many studies (Abrams and Ruffner 1995, Abrams 2000, Black et al. 2006, Johnson 2013, Abrams and Nowacki 2019) have used historical

vegetation records to determine that oak-dominated forests were common prior to European settlement. However, we have limited historical data

for the distribution for red oak-dominated forests in Pennsylvania. Some authors have suggested that red oak and other species may be replacing

historically dominant species, such as white oak, hickory, white pine and American chestnut in the absence of fire or other disturbance in certain ecoregions

(Abrams and Ruffner 1995, Abrams 2000, Black et al. 2006, Johnson 2013, Abrams and Nowacki 2019)

Invasive plant species do not seem to be a major issue without significant disturbance to the canopy or soil. However, spongy moth mortality

and other canopy-altering disturbance events may enable invasive plants to thrive following establishment. Limestone gravel roads and trails

and alterations to site hydrology my facilitate establishment of invasive plants such as Japanese stilt-grass (Microstegium vimineum)

(Rauschert and Nord 2010, Nord and Mortensen 2010).

Development of natural gas and pipeline rights-of-way threaten the ecological integrity of large unfragmented patches of this community

and reduce the size and contiguousness of occurrences.

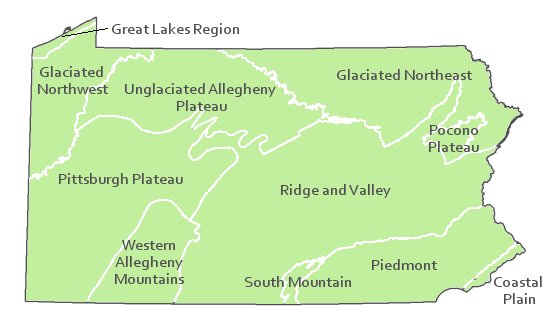

Range Map

Pennsylvania Range

This community occurs in all regions of Pennsylvania and is common, except for in the Western Allegheny Plateau and Glaciated Northwest (EPA Erie Drifts Ecoregion (61)) where it is limited to dry, south-facing ridge tops and represented by the NVC Association CEGL005023. It is much more common in the Ridge and Valley, High Allegheny Plateau, and Allegheny Mountains Regions where it is represented by the other four associations. The associations listed in the NVC are regional varieties, but represent oak-dominated communities with a significant understory of ericaceous shrub species, indicating dry, acidic soils.

Global Distribution

These forests are associated with the Central Appalachians, and generally follow the distribution of Braun’s Appalachian Oak Region (Braun 1950), with representative associations occurring from Virginia to Massachusetts.

Abrams MD, Nowacki GJ. 2019. Global change impacts on forest and fire dynamics using paleoecology and tree census data for eastern North America. Annals of Forest Science 76:8.

Abrams MD, Ruffner CM. 1995. Physiographic analysis of witness-tree distribution (1765-1798) and present forest cover through north central Pennsylvania. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 25:659-668.

Abrams MD. 2000. Fire and the ecological history of oak forests in the eastern United States. Page 46 Proceedings: Workshop on Fire, People, and the Central Hardwoods Landscape. USDA Forest Service Northeastern Research Station, Richmond, KY.

Black BA, Ruffner CM, Abrams MD. 2006. Native American influences on the forest composition of the Allegheny Plateau, northwest Pennsylvania. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 36:1266-1275.

Braun EL. 1950. Deciduous forests of eastern North America. Blakiston, the University of California.

Diller JD. 1965. Chestnut Blight. Forest Pest Leaflet 94, Vol. 94 Washington, D.C. USDA Forest Service. Available from https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/fsbdev2_043617.pdf.

Johnson SE. 2013. Native American land use legacies in the present day landscape of the Eastern United States. Ph.D. Dissertation. Pennsylvania State University.

McManus MN, Scheebergerm N, Reardon R, Mason G. 1980. Gypsy Moth. Forest Insect and Disease Leaflet 162. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Washington, D.C.

Nord A, Mortensen D. 2010. Use of limestone gravel on forest roads increases abundance of Microstegium vimineum (Japanese stiltgrass).

Perles S, Furedi M, Eichelberger B, Feldman A, Edinger GJ, Eastman E, Sneddon L. 2008. Vegetation Classification and Mapping at Upper Delaware Scenic and Recreational River. Natural Resource Technical Report. Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR-2008/133. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Philadelphia, PA.

Perles S, Podniesinski GS, Eastman E, Sneddon, LA, Gawler SC. 2007a. Classification and Mapping of Vegetation and Fire Fuel Models at Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area: Volumes 1 and 2. Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR-2007/076. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Philadelphia, PA.

Perles S, Podniesinski GS, Millinor WA, Sneddon, LA. 2006a. Vegetation classification and mapping at Gettysburg National Military Park and Eisenhower National Historic Park. Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR--2006/058. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Philadelphia, PA.

Perles S, Podniesinski GS, Zimmerman E, Eastman E, Sneddon L. 2007b. Vegetation Classification and Mapping at Allegheny Portage Railroad National Historic Site [and associated files]. Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR-2006/079. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Philadelphia, PA.

Perles S, Podniesinski GS, Zimmerman E, Millinor WA, Sneddon L. 2006b. Vegetation Classification and Mapping at Friendship Hill National Historic Site Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR--2006/041. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Philadelphia, PA.

Perles S, Podniesinski GS, Zimmerman E, Millinor WA, Sneddon L. 2006c. Vegetation Classification and Mapping at Fort Necessity National Battlefield. Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR-2006/038. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Philadelphia, PA.

Perles S, Podniesinski GS, Zimmerman E, Millinor WA, Sneddon L. 2006d. Vegetation Classification and Mapping at Johnstown Flood National Memorial. Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR-2006/034. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Philadelphia, PA.

PGC-PFBC (Pennsylvania Game Commission and Pennsylvania Fish & Boat Commission). 2015. Pennsylvania Wildlife Action Plan 2015-2025. Pennsylvania Game Commission and Pennsylvania Fish & Boat Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Available from http://www.fishandboat.com/Resource/StateWildlifeActionPlan/Pages/default.aspx (accessed April 16, 2018).

Podniesinski G, Perles S, Sneddon L, Millinor WA. 2005. Vegetation Classification and Mapping of Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site. Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR-2005/012. Page 107. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Northeast Region. Philadelphia, PA. Available from https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/622093.

Rauschert ESJ, Nord AN. 2010. Japanese stiltgrass: an invasive on the move. The Ohio Woodland Journal 17:15-17.

Sargent S, Yeany III D, Michel N, Zimmerman E. 2017. Forest Interior Bird Habitat Relationships in the Pennsylvania Wilds, Final Report for WRCP-14507. Audubon Pennsylvania, National Audubon Society.

Cite as:

Braund, J. and E. Zimmerman. 2022. Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program. Dry Oak - Heath Forest Factsheet. Available from: https://naturalheritage.state.pa.us/Community.aspx?=16059 Date Accessed: February 10, 2026