Golden Saxifrage – Sedge Rich Seep

System: Palustrine

Subsystem: Herbaceous

PA Ecological Group(s): Seepage Wetland

Global Rank:GNR

![]() rank interpretation

rank interpretation

State Rank: S2

General Description

This community occurs in small (less than 0.5 hectare) patches, fed by groundwater seepage. The species composition is diverse and variable. Wetlands that are more open will tend to be dominated by graminoids, while wetlands shaded by forest canopy will tend to be dominated by broad-leaved plants. It may occur as part of a fen wetland complex, in areas of active seepage flow, often around edges. Plants of seepage habitats represent a broad range of pH tolerances, including Pennsylvania bittercress (Cardamine pensylvanica), golden ragwort (Packera aurea), jewelweed (Impatiens spp.), skunk-cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus), golden saxifrage (Chrysosplenium americanum), New York ironweed (Vernonia noveboracensis), field horsetail (Equisetum arvense), swamp saxifrage (Saxifraga pensylvanica), sedge (Carex leptalea), and turtlehead (Chelone glabra). Some of the following indicators of more alkaline pH should also be present: yellow sedge (Carex flava), Atlantic sedge (Carex sterilis), thin-leaved cotton-grass (Eriophorum viridicarinatum), capillary beak-rush (Rhynchospora capillacea), grass-of-Parnassus (Parnassia glauca), brook lobelia (Lobelia kalmii). Stoneworts (Chara spp.), an aquatic algae that resembles an aquatic plant, may cover areas of open seepage. Other species may include bog sedge (Carex atlantica), sedge (Carex granularis), fowl bluegrass (Poa palustris), water horsetail (Equisetum fluviatile), white beak-rush (Rhynchospora alba), and marsh fern (Thelypteris palustris).

Rank Justification

Imperiled in the jurisdiction because of rarity due to very restricted range, very few populations, steep declines, or other factors making it very vulnerable to extirpation.

Identification

- Presence of seepage (diffuse ground-water fed upwelling of water that does not coalesce into a free-flowing channel)

- Calcareous species such as golden ragwort (Packera aurea), golden saxifrage (Chrysosplenium americanum), yellow sedge (Carex flava), Atlantic sedge (Carex sterilis), capillary beak-rush (Rhynchospora capillacea), grass-of-Parnassus (Parnassia glauca), and brook lobelia (Lobelia kalmii)

- Relatively more open than the Skunk Cabbage – Golden Saxifrage Forest Seep, unlikely to have skunk cabbage as a community dominant

Herbs

- Yellow sedge (Carex flava)

- Atlantic sedge (Carex sterilis)

- Capillary beak-rush (Rhynchospora capillacea)

- Grass-of-parnassus (Parnassia glauca)

- Brook lobelia (Lobelia kalmii)

- Pennsylvania bittercress (Cardamine pensylvanica)

- Golden ragwort (Packera aurea)

- Jewelweed (Impatiens capensis)

- Skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus)

- Golden saxifrage (Chrysosplenium americanum)

- New York ironweed (Vernonia noveboracensis)

- Field horsetail (Equisetum arvense)

- Swamp saxifrage (Saxifraga pensylvanica)

- Turtlehead (Chelone glabra)

* limited to sites with higher soil calcium

Vascular plant nomenclature follows Rhoads and Block (2007). Bryophyte nomenclature follows Crum and Anderson (1981).

International Vegetation Classification Associations:

USNVC Crosswalk:None

Representative Community Types:

Mid-Atlantic Rich Seep (CEGL006448)

NatureServe Ecological Systems:

None

NatureServe Group Level:

None

Origin of Concept

Fike, J. 1999. Terrestrial and palustrine plant communities of Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Natural Diversity Inventory. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Recreation, Bureau of Forestry, Harrisburg, PA. 86 pp.

Pennsylvania Community Code*

HX : Golden Saxifrage – Sedge Rich Seep

*(DCNR 1999, Stone 2006)

Similar Ecological Communities

Seep communities are differentiated from the Golden Saxifrage – Pennsylvania Bittercress Spring Run because seepages are diffuse groundwater flow, while Golden Saxifrage – Pennsylvania Bitter-cress Spring Run has groundwater flow that coalesces into a recognizable channel. Generally, the volume of springs is also higher. This seep community may occur as part of a fen complex, and is differentiated from the shrub and sedge fen communities by the presence of active seepage flow, in high enough volume to be visible and usually to prevent peat accumulation. This community can be differentiated from the Skunk-cabbage – Golden Saxifrage Seep because it tends to be more open, and skunk-cabbage will not be the dominant species.

Fike Crosswalk

Golden Saxifrage – Sedge Rich Seep

Conservation Value

The Golden Saxifrage – Sedge Rich Seep occurs where mineral-enriched, circumneutral pH groundwater reaches the surface, which is an especially unusual condition in Pennsylvania as the predominant geology in most regions is acidic. Plants of special concern in Pennsylvania found in this habitat include yellow sedge (Carex flava), Atlantic sedge (Carex sterilis), capillary beak-rush (Rhynchospora capillacea), grass-of-Parnassus (Parnassia glauca), brook lobelia (Lobelia kalmii), thin-leaved cotton-grass (Eriophorum viridicarinatum), and sedge (Carex tetanica).

Threats

The greatest threats to these communities are groundwater extraction and bedrock disruptions such as drilling or mining in nearby areas, which can contaminate or alter the flow patterns of the groundwater that feeds the seepage. Groundwater pollution can also occur from improperly installed septic systems, improperly lined underground waste disposal, and in agricultural areas, infiltration of pesticides, fertilizer, and bacteria from animal wastes. Removal of natural vegetation cover adjacent to the wetland can affect water levels and temperatures by increasing solar heating, surface run-off, and sedimentation. Invasive plant species can threaten the biological integrity of the community.

Management

Extraction, drilling, mining, or other activities that impact the bedrock or flow of groundwater should not be undertaken within half a mile of a seepage wetland without a thorough understanding of bedrock layers and groundwater flows. Groundwater flow patterns do not always mirror surface watersheds, and in some cases aquifers may be contiguous over large areas. Seepage wetlands are also sensitive to trampling and other physical disturbance from recreational activities; trails should be sited away from the wetland, or elevated structures employed to prevent traffic in the wetland. A natural buffer around the wetland should be maintained in order to minimize nutrient runoff, pollution, and sedimentation. The potential for soil erosion based on soil texture, condition of the adjacent vegetation (mature forests vs. clearcuts), and the topography of the surrounding area (i.e., degree of slope) should be considered when establishing buffers. The buffer size should be increased if soils are erodible, adjacent vegetation has been logged, and the topography is steep as such factors could contribute to increased sedimentation and nutrient pollution. Direct impacts and habitat alteration should be avoided (e.g., roads, trails, filling of wetlands) and low impact alternatives (e.g., elevated footpaths, boardwalks, bridges) should be utilized in situations where accessing the wetland cannot be avoided. Care should also be taken to control and prevent the spread of invasive species within the wetland. Alterations to groundwater sources should be minimized.

Research Needs

Groundwater flows are not well understood in many areas, and this information is very useful in managing seepage wetlands. Management may also be improved with a better understanding of natural successional pathways in these wetlands.

Trends

Specific information on the loss and degradation of the calcareous seepage wetlands that host the Golden Saxifrage – Sedge Rich Seep community is not available.

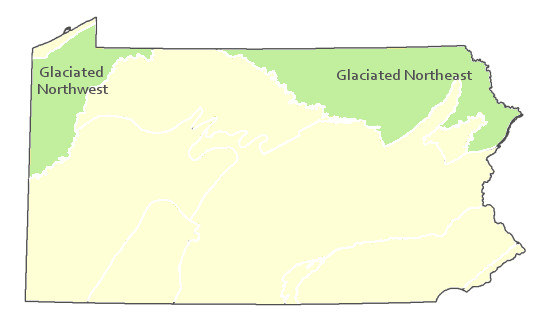

Range Map

Pennsylvania Range

Northwest and northeast Pennsylvania.

Global Distribution

New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania

Byers, E. A., J. P. Vanderhorst, and B. P. Streets. 2007. Classification and conservation assessment of high elevation wetland communities in the Allegheny Mountains of West Virginia. West Virginia Natural Heritage Program, West Virginia Division of Natural Resources, Elkins.

CAP [Central Appalachian Forest Working Group]. 1998. Central Appalachian Working group discussions. The Nature Conservancy, Boston, MA.

Clancy, K. 1996. Natural communities of Delaware. Unpublished review draft. Delaware Natural Heritage Program, Division of Fish and Wildlife, Delaware Division of Natural Resources and Environmental Control, Smyrna, DE. 52 pp.

Cowardin, L. M., V. Carter, F. C. Golet, and E. T. LaRoe. 1979. Classification of wetlands and deepwater habitats of the United States. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Biological Service Program. FWS/OBS-79/31. Washington, DC. 103 pp.

Dahl, T.E. 1990. Wetlands losses in the United States 1780's to 1980's. U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service. Washington, D.C. http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov/resource/othrdata/wetloss/wetloss.htm (Version 16JUL97).

Dahl, T.E. 2006. Status and trends of wetlands in the conterminous United States 1998 to 2004. U.S. Department of the Interior; Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C. 112 pp.

Eastern Ecology Working Group of NatureServe. No date. International Ecological Classification Standard: International Vegetation Classification. Terrestrial Vegetation. NatureServe, Boston, MA.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero, editors. 2002. Ecological communities of New York state. Second edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's ecological communities of New York state. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY.

Fike, J. 1999. Terrestrial and palustrine plant communities of Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Natural Diversity Inventory. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Recreation. Bureau of Forestry. Harrisburg, PA. 86 pp.

Fleeger, G. M., 1999, The geology of Pennsylvania’s groundwater

(3rd ed.): Pennsylvania Geological Survey, 4th ser.,

Educational Series 3, 34 p. http://www.dcnr.dcnr.pa.gov/topogeo/education/es3.pdf

Gawler, S. C. 2002. Natural landscapes of Maine: A guide to vegetated natural communities and ecosystems. Maine Natural Areas Program, Department of Conservation, Augusta, ME. [in press]

Harrison, J. W., compiler. 2004. Classification of vegetation communities of Maryland: First iteration. A subset of the International Classification of Ecological Communities: Terrestrial Vegetation of the United States, NatureServe. Maryland Natural Heritage Program, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Annapolis. 243 pp.

Helfrich, L.A., J. Parkhurst, and R. Neves. 2009. Managing spring wetlands for fish and wildlife habitat. Virginia Cooperative Extension publication 420-537. http://pubs.ext.vt.edu/420/420-537/420-537.html

Hill, A. F. 1923. The vegetation of the Penobscot Bay region, Maine. Proceedings of the Portland Society of Natural History 3:307-438.

NatureServe 2010. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, VA. Available http://www.natureserv.org/explorer (accessed: 23 November 2011).

Northern Appalachian Ecology Working Group. 2000. Northern Appalachian / Boreal Ecoregion community classification (Review Draft). The Nature Conservancy, Eastern Conservation Science Center, Boston, MA. 117 pp. plus appendices.

Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR). 1999. Inventory Manual of Procedure. For the Fourth State Forest Management Plan. Pennsylvania Bureau of Forestry, Division of Forest Advisory Service. Harrisburg, PA. 51 ppg.

Sperduto, D. D. 2000b. A classification of wetland natural communities in New Hampshire. New Hampshire Natural Heritage Inventory, Department of Resources and Economic Development, Division of Forests and Lands. Concord, NH. 156 pp.

Stone, B., D. Gustafson, and B. Jones. 2006 (revised). Manual of Procedure for State Game Land Cover Typing. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Game Commission, Bureau of Wildlife Habitat Management, Forest Inventory and Analysis Section, Forestry Division. Harrisburg, PA. 79 ppg.

Swain, P. C., and J. B. Kearsley. 2000. Classification of natural communities of Massachusetts. July 2000 draft. Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife. Westborough, MA.

Thompson, E. 1996. Natural communities of Vermont uplands and wetland. Nongame and Natural Heritage Program, Department of Fish and Wildlife in cooperation with The Nature Conservancy, Vermont chapter. 34 pp.

Thompson, E. H., and E. R. Sorenson. 2000. Wetland, woodland, wildland: A guide to the natural communities of Vermont. The Nature Conservancy and the Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife. University Press of New England, Hanover, NH. 456 pp.

Tiner, R.W. 1990. Pennsylvania’s Wetlands: Current Status and Recent Trends. U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service report, 104 pp.

Cite as:

Mcpherson, J. 2022. Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program. Golden Saxifrage – Sedge Rich Seep Factsheet. Available from: https://naturalheritage.state.pa.us/Community.aspx?=16005 Date Accessed: February 27, 2026