Lizard's-tail Emergent Bed

System: Palustrine

Subsystem: Herbaceous

PA Ecological Group(s): River Floodplain

Global Rank:G2G3

![]() rank interpretation

rank interpretation

State Rank: S4

General Description

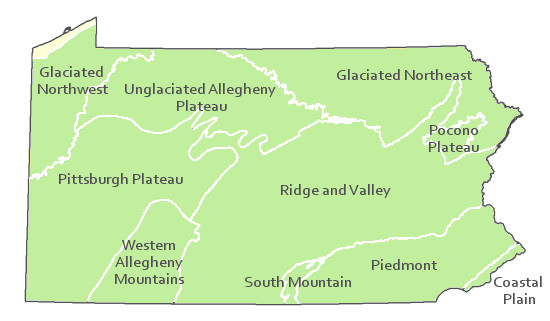

This community is found along river floodplains throughout Pennsylvania, most commonly in the Juniata and Susquehanna River drainages and the smaller tributaries of the main stem of the Susquehanna in the Ridge and Valley Province. The emergent beds typically occur near bars, islands, and river banks, or in shallow portions of the river channel where silt accumulates. It can also be found in back-channels, abandoned oxbow wetlands and other wet depressions on river floodplains. The lower portion of the lizard’s-tail stems are under water for most of the year, with the tops of the plants emerging above the flowing water. These beds are frequently submerged during flood events.

Lizard’s-tail (Saururus cernuus) is the dominant species in this community, often forming single-species beds. Many other species may be present, including water-willow (Justicia americana), water smartweed (Persicaria amphibia), marsh-purslane (Ludwigia palustris), purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), annual bluegrass (Poa annua), false nettle (Boehmeria cylindrica), clearweed (Pilea pumila), garden loosestrife (Lysimachia vulgaris), rice cutgrass (Leersia oryzoides), beggar-ticks (Bidens frondosa), threesquare (Schoenoplectus pungens), and nutsedges (Cyperus spp.). A few scattered silver maple (Acer saccharinum) seedlings may also be present.

Rank Justification

Uncommon but not rare; some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors.

Identification

- Dominated by lizard’s-tail (Saururus cernuus), often growing in large, monotypic beds

- Sites are often inundated most of the year

- Maintained by annual episodes of high intensity flooding and ice scour

Herbs

- Lizard's-tail (Saururus cernuus)

- Water-willow (Justicia americana)

- Water smartweed (Persicaria amphibia)

- Marsh-purslane (Ludwigia palustris)

- Purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria)

- Annual bluegrass (Poa annua)

- False nettle (Boehmeria cylindrica)

- Clearweed (Pilea pumila)

- Garden loosestrife (Lysimachia vulgaris)

- Rice cutgrass (Leersia oryzoides)

- Beggar-ticks (Bidens frondosa)

- Threesquare (Schoenoplectus pungens)

- Nutsedges (Cyperus spp.)

* limited to sites with higher soil calcium

Vascular plant nomenclature follows Rhoads and Block (2007). Bryophyte nomenclature follows Crum and Anderson (1981).

International Vegetation Classification Associations:

USNVC Crosswalk:None

Representative Community Types:

Floodplain Pool (CEGL007696)

NatureServe Ecological Systems:

Central Appalachian River Floodplain (CES202.608)

NatureServe Group Level:

None

Origin of Concept

Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program. 2004. Classification, Assessment and Protection of Non-Forested Floodplain Wetlands of the Susquehanna Drainage. Report to: The United States Environmental Protection Agency and the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Forestry, Ecological Services Section. US EPA Wetlands Protection State Development Grant no. CD-98337501., Zimmerman 2008

Pennsylvania Community Code*

na : Not Available

*(DCNR 1999, Stone 2006)

Similar Ecological Communities

Periodically Exposed Shoreline Community community patches contain a wider variety of plant species, often weedy or non-native plants. Lizard’s-tail Emergent Beds are often inundated for longer periods of time than the Periodically Exposed Shoreline Community community patches.

Water-willow (Justicia americana) is dominant in Water-willow Emergent Bed communities. Water-willow Emergent Bed are more typically found in faster moving, high energy systems.

Fike Crosswalk

None; this type is new to the Pennsylvania Plant Community Classification developed from river floodplain classification studies in the Susquehanna River Basin.

Conservation Value

Although considered common, this community provides important habitat for a number of important and rare insect species which require submerged aquatic vegetation for foraging habitat, which may be limited in flowing water systems. Emergent beds are important habitat for larval life stages of mayflies, damselflies, and dragonflies.

Threats

Within floodplain ecosystems, alteration to the frequency and duration of flood events and development of the river floodplains are the two greatest threats to this community statewide and can lead to habitat destruction and/or shifts in community function and dynamics. Non-native invasive plants may be equally devastating as native floodplain plants are displaced. Invasive non-native plants, such as purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), commonly dominate this community, especially near human development. Construction of flood-control and navigational dams have resulted in drastic changes to the timing and duration of flood events.

Management

Direct impacts and habitat alteration should be avoided (e.g., roads, trails, filling of wetlands). Care should also be taken to control and prevent the spread of invasive species into these wetlands.

Research Needs

In addition to further studying the range of this type, there is need to monitor high quality examples of this community. Large expanses of this type should be inventoried for rare plants and animals, especially insects.

Trends

There is little to suggest that this type is increasing or decreasing in occurrence. Invasive plants able to tolerate flooded conditions may gain a foothold in these sites and contribute to an overall reduction in quality region-wide. Sites near urban areas are most invaded.

Range Map

Pennsylvania Range

Statewide, except the Great Lakes region.

Global Distribution

Unknown

Cowardin, L.M., V. Carter, F.C. Golet, and E.T. La Roe. 1979. Classification of wetlands and deepwater habitats of the United States. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Washington, D.C. 131 pp.

Fike, J. 1999. Terrestrial and palustrine plant communities of Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Natural Diversity Inventory. Harrisburg, PA. 86 pp.

NatureServe. 2009. International Ecological Classification Standard: International Vegetation Classification. Central Databases. NatureServe, Arlington, VA. Available http://www.natureserve.org/explorer.

Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR). 1999. Inventory Manual of Procedure. For the Fourth State Forest Management Plan. Pennsylvania Bureau of Forestry, Division of Forest Advisory Service. Harrisburg, PA. 51 ppg.

Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program. 2004. Classification, Assessment and Protection of Non-Forested Floodplain Wetlands of the Susquehanna Drainage. Report to: The United States Environmental Protection Agency and the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Forestry, Ecological Services Section. US EPA Wetlands Protection State Development Grant no. CD-98337501.

Stone, B., D. Gustafson, and B. Jones. 2006 (revised). Manual of Procedure for State Game Land Cover Typing. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Game Commission, Bureau of Wildlife Habitat Management, Forest Inventory and Analysis Section, Forestry Division. Harrisburg, PA. 79 ppg.

Zimmerman, E., and G. Podniesinski. 2008. Classification, Assessment and Protection of

Floodplain Wetlands of the Ohio Drainage. Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program, Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, Pittsburgh, PA. Report to: The United States Environmental Protection Agency and the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Office of Conservation Science. US EPA Wetlands Protection State Development Grant no. CD-973081-01-0.

Cite as:

Zimmerman, E. 2022. Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program. Lizard's-tail Emergent Bed Factsheet. Available from: https://naturalheritage.state.pa.us/Community.aspx?=30012 Date Accessed: February 27, 2026