Dry Oak – Heath Woodland

System: Terrestrial

Subsystem: Woodland

PA Ecological Group(s):

Central Appalachian – Northeast Oak Forest & Woodland

Global Rank:G4G5

![]() rank interpretation

rank interpretation

State Rank: S3

General Description

This is a community with an open canopy (less than 60% canopy cover) found on dry, thin, acidic soils over sandstone bedrock. Dominant trees include chestnut oak (Quercus montana), red oak (Q. rubra), scarlet oak (Q. coccinea), black oak (Q. velutina), blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), sassafras (Sassafras albidum), sweet birch (Betula lenta), gray birch (B. populifolia), and red maple (Acer rubrum). Eastern white pine (Pinus strobus) and pitch pine (P. rigida) or occasionally other dry-site pines may be present but contribute less than 25% of the tree stratum. The structure of the shrub layer is variable; it may be composed entirely of low shrubs like black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata), low sweet blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium), lowbush blueberry (V. pallidum), sweet fern (Comptonia peregrina), and teaberry (Gaultheria procumbens), or there may be an additional layer of taller shrubs like mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia), and scrub oak (Quercus ilicifolia). Typical herbaceous species include bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum), Canada mayflower (Maianthemum canadense), poverty grass (Danthonia spicata), cow-wheat (Melampyrum lineare), Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica), a sedge (C. communis), wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis), trailing arbutus (Epigaea repens), spreading ricegrass (Oryzopsis asperifolia).

This type often occurs adjacent to the Pitch Pine - Heath Woodland type, along lower ridgetops, or on other dry sites. This community may also occur on ridgetop acidic barrens sites, associated with other acidic barrens communities in the Ridgetop Acidic Barren Complex.

The Dry Oak – Rocky Woodland is further defined by three subtypes based on tree species dominance and topographic position. One of the subtypes is found on low to mid-elevation summits and south facing upper slopes from New England to the highest peaks in West Virginia. The canopy features scattered, stunted trees and is mainly comprised of red oak. Minor tree associates include black oak, chestnut oak, sweet birch, and red maple. Pines are only present in small amounts. Another subtype is mainly restricted to upper slopes and ridgetops and features a co-dominance between chestnut and red oak. This type occurs from central and southern New England south to the northern Piedmont and central Appalachians. The third subtype is restricted to the Appalachian National Scenic Trail in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. This type has a clear dominance of pignut hickory (Carya glabra) and has a similar heath shrub layer as the other types.

Rank Justification

The Dry Oak – Rocky Woodland is vulnerable to extirpation in the jurisdiction due to a restricted range, relatively few occurrences (often 80 or fewer), and recent and widespread declines. This community type is relatively uncommon, typically occurs in small- to medium-sized patches and is vulnerable to forest succession without active management. It is also fire-dependent and in decline due to widespread fire suppression over much of the last century.

The Lower New England High Slope Chestnut Oak Forest (CEGL006282) and the Red Oak / Heath Woodland Rocky Summit (CEGL006134) are the two most common subtypes of the Dry Oak – Rocky Woodland in Pennsylvania. The Ridgetop Pignut Hickory Woodland (CEGL006640) is only known from the ridgetops of the Appalachian National Scenic Trail in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. This type is not ranked currently and may be under-surveyed.

Identification

- Occurs on dry, sandy, acidic soils

- Total tree canopy cover is between 10% - 60%

- Total cover of pitch pine and other conifers is less than 25% in combined canopy and subcanopy strata

- Tree canopy is dominated by dry-site oaks

- Shrub layer is dominated by various heath species, possibly including tall species like mountain laurel or scrub oak

Trees

Shrubs

Herbs

Bryophytes

* limited to sites with higher soil calcium

Vascular plant nomenclature follows Rhoads and Block (2007). Bryophyte nomenclature follows Crum and Anderson (1981).

International Vegetation Classification Associations:

USNVC Crosswalk:

Northeast Oak Rocky Woodland (A4467)

Red Oak / Heath Woodland Rocky Summit (CEGL006134)

Lower New England High Slope Chestnut Oak Forest (CEGL006282)

Ridgetop Pignut Hickory Woodland (CEGL006640)

NatureServe Ecological Systems:

None

NatureServe Group Level:

Central Appalachian – Northeast Oak Forest & Woodland (G650)

Origin of Concept

Fike, J. 1999. Terrestrial and palustrine plant communities of Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Natural Diversity Inventory. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Recreation, Bureau of Forestry, Harrisburg, PA. 86 pp.

Gawler, S. C., Neid, S. L., and Largay, E. 2018. Red Oak / Heath Woodland Rocky Summit (CEGL006134). NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. (Accessed: January 12, 2022).

Gleming, G., Coulling, P., Neid, S. L., Sneddon, L. A., and Gawler, S.C. 2006. Lower New England High Slope Chestnut Oak Forest (CEGL006282). NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. (Accessed: January 12, 2022).

Largay, E. and Russo, M. 2018. Ridgetop Pignut Hickory Woodland (CEGL006640). NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. (Accessed: January 12, 2022).

Pennsylvania Community Code*

JA : Dry Oak – Heath Woodland

*(DCNR 1999, Stone 2006)

Similar Ecological Communities

The Dry Oak – Rocky Woodland may occur alongside others in the Ridgetop Acidic Barrens Complex. The barrens types represent a group of communities with open-canopies found on high elevation ridgetops and summits (350m – 670m), where low soil moisture, shallow soils, high wind velocities, frequent fires, and usually a history of cutting have limited tree growth.

This type is similar to the Pitch Pine – Heath Woodland and the Dry Oak – Heath Forest. It is distinguished from the Pitch Pine – Heath Woodland in that it lacks a substantial conifer component (less than 25% relative cover in the combined canopy and subcanopy layers) and from the Dry Oak – Heath Forest by having an open canopy (less than 60% cover by trees).

This community often co-occurs with several other types in the Ridgetop Acidic Barrens Complex:

- Dry Oak – Rocky Woodland

- Red Spruce Rocky Summit (rare; confined to high elevations)

- Scrub Oak Shrubland

- Low Heath Bedrock Outcrop (confined to high elevation)

- Little Bluestem – Pennsylvania Sedge Opening

- Pitch Pine – Heath Woodland

- Pitch Pine – Scrub Oak Woodland

The communities that create the Ridgetop Acidic Barrens Complex form a mosaic that are related by successional stage. The herbaceous types occur more sporadically throughout shrubland, woodland, and forest types based on time since fire, clearcutting, or other disturbance. The arrangement of different types within a site, and the pace of succession, is also determined by differences in environmental variables such as aspect, soil depth, elevation, exposure, and microclimate. In general, the physiognomy becomes more open at higher elevations and on southern exposures. Where fires are frequent, pitch pine will typically be present. In the absence of fire, other pines (white pine, Virginia pine, shortleaf pine, or Table Mountain pine) may accompany or replace pitch pine, or pine may be absent altogether. Frost pockets may play a role in maintaining open areas; this is especially true of the Little Bluestem – Pennsylvania Sedge Opening type. Long-term fire suppression may cause the distinctive vegetation of the herbaceous openings to give way to more mesic species typical of the surrounding forests at lower elevations.

The forest types that most typically surround these communities are the Dry Oak – Heath Forest and Pitch Pine – Mixed Oak Forest.

Fike Crosswalk

Dry Oak – Heath Woodland

Conservation Value

Acidic barrens communities can host a number of rare plant species and an exceptional diversity of rare butterflies, moths, and other insects. Barrens communities can arise as a result of a variety of human-induced and natural disturbances; many have their origin in the 19th or 20th century, while others have persisted longer through a combination of periodic human-induced disturbance dating to pre-settlement times and edaphic factors (Copenheaver et al., 2000; Kurczewski, 1999; Latham, 2003; Motzkin & Foster, 2002). Latham (2003) suggests that the diversity and presence of rare plant species in barrens is correlated with the overall age of the barrens, with newer barrens less likely to host rare plants. Animal diversity appears to be less sensitive to age; perhaps because many of these species are highly mobile.

Both plant and lepidopteran species can be sensitive to successional stage and time since disturbance; some require very open, grassy areas, while others can also inhabit shrublands and woodlands with partial shade. The species of conservation value are not necessarily indicator species for the community type, and may also occupy other types of habitat, but barrens sites are one of the habitats important for their conservation.

Species of great conservation value that are associated with barrens include many species of Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies) which have barrens plants as hosts, plants that can withstand the acidic, thin soils, and vertebrate species who thrive with hot, dry conditions. Examples of invertebrates that can be found in barrens include waxed sallow moth (Chaetaglaea cerata; G3G4/S2S3), twilight moth (Lycia rachelae; G5/S2?), and flypoison borer moth (Papaipema sp. 1; G2G3/S2S3). The timber rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus; G4/S2S3) and eastern hognose snake (Heterodon platirhinos; G5/S3S4) can utilize barrens. A few plant species that are associated with barrens include variable sedge (Carex polymorpha; G3/S2), dwarf iris (Iris verna; G5/S1), and sand blackberry (Rubus cuneifolius; G5/S1).

Threats

The primary threats to acidic barrens communities are succession and fire suppression. Many of the unique species that inhabit these barrens are most successful in the early stages of succession, such as grasslands and open shrublands, and are therefore particularly vulnerable to the effects of succession over the long-term. Pitch pine are known to not germinate and establish well without fire.

Spongy moth (Lymantria dispar) outbreaks also threaten barrens, which often have a strong component of oak species in the tree and shrub layers. However, spongy moth control agents can also threaten the unique butterfly and moth species that inhabit barrens.

Studies across a number of sites in New England and Pennsylvania demonstrate that many barrens are disturbance-dependent ecosystems that, in the absence of disturbance, move through succession to forest rapidly (Copenheaver et al., 2000; Kurczewski, 1999; Latham, 2003; Motzkin & Foster, 2002). These studies have observed similar patterns of barrens succession to forest, sometimes even mesic forest, in recent decades.

Changes in land use and fire suppression over the last century are at the root of these patterns of succession. Through meticulous efforts to identify historic land use and changes in vegetation over time, researchers have documented that barrens are correlated with areas that burned frequently; primarily from Native American use of fire and railroads. The cessation of these land use practices, and the advent of widespread, long-term fire suppression, is correlated with succession of grasslands and open shrublands to dense shrub thickets and forests. Charcoal production retards vegetation such that former hearths resemble barrens, but it appears the mechanism is a more profound and persistent alteration of soil chemistry.

The Dry Oak – Rocky Woodland is also threatened by the southern pine beetle (Dendroctonus frontalis). The southern pine beetle is a native beetle of the southeastern United States that feeds primarily on pines such as pitch, shortleaf, Virginia, and white. Outbreaks occur every 6-12 years and can last for 2-3 years. The southern pine beetle feeds on phloem in the inner bark, which ultimately girdles and kills the tree (Liu, n.d.). Additionally, the southern pine beetle has experienced an unprecedented northward expansion in recent years due to mild winters and climate models predict the range to expand to almost the entirety of Pennsylvania (aside from much of the Northern Allegheny Plateau) by 2050, and north into Canada by 2080 (Lesk et al., 2017). The southern pine beetle does not currently overlap with the native range of this community type, however it is considered a serious long-term threat. This community type may also be impacted by the spotted lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula). The spotted lanternfly is newly established in Pennsylvania and has been found to lay eggs and feed on a number of common hardwood trees in Pennsylvania, but has not been found to cause tree mortality (Barringer & Ciafré, 2020). This invasive pest may weaken hardwood associate trees in this type but may only represent a small threat since hardwood trees are not dominant.

Other threats include loss of this community due to development of cell phone towers, wind turbines, and utility lines, or trampling by visitors on ATVs.

Management

It is important to develop a site-wide management plan at acidic barrens to maintain multiple successional stages. Fire is the optimal tool for barrens management. Where it is not feasible to use fire as a management tool, a combination of cutting and soil scarification can be used to mimic its effects.

Plans should also consider specific needs of barrens indicator species and rare species. To avoid severe reduction of lepidopteran populations, prescribed burning should not be undertaken across an entire site at once; in a given year, unburned areas should be left as refugia for these species.

Spongy moth control programs should balance maintenance of oaks and lepidopterans, using control agents specific to the spongy moth where possible, or leaving some untreated areas as refugia for native lepidopteran populations.

Research Needs

Site-specific research into historical land management, fire frequency, and vegetation patterns has greatly enhanced \understanding of barrens systems at other locations in the northeastern region, but very few Pennsylvania sites have been studied. The origins and timeline of many of our barrens sites in Pennsylvania remains unknown.

There is a need to adapt and/or develop management techniques specialized to this region and its species of concern. In some areas, barrens have completely succeeded to forest. Research should focus on identifying specifically where shrub and herbaceous barrens once existed, identifying characteristics of optimal restoration sites, and identifying successful management techniques for restoring the herbaceous and shrub component of barrens mosaics.

Plot data is currently limited on the CEGL006134 and CEGL006640 subtypes. Future research should focus on collecting data on these types.

Trends

Barrens ecosystems have declined due to succession and fire suppression in recent decades. Rare species that are particularly dependent on open barrens habitats have also declined across Pennsylvania.

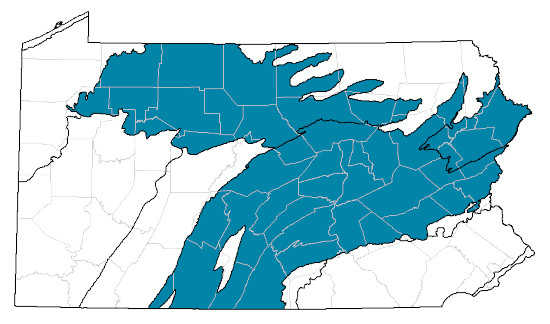

Range Map

Pennsylvania Range

This community type is widespread yet relatively uncommon. The Lower New England High Slope Chestnut Oak Forest (CEGL006282) and the Red Oak / Heath Woodland Rocky Summit (CEGL006134) are the most common subtypes of the Dry Oak – Rocky Woodland in Pennsylvania, while the Ridgetop Pignut Hickory Woodland (CEGL006640) is only known from the ridgetops of the Appalachian National Scenic Trail in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. The Dry Oak – Rocky Woodland can be found in the North Central Appalachians, Central Appalachians, Northern Piedmont and Ridge and Valley ecoregions within Pennsylvania (USEPA Level III).

There are over 55 plots of this community type sampled in Pennsylvania (Figure 1.)

Global Distribution

Connecticut, Maine, ME, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Vermont, Delaware, Maryland, Rhode Island, Virginia, West Virginia

Barringer, L., & Ciafré, C. M. (2020). Worldwide feeding host plants of spotted lanternfly, with significant additions from North America. Environmental Entomology, 49(5), 999-1011.

Copenheaver, C. A., White, A. S., & William A. Patterson III. (2000). Vegetation Development in a Southern Maine Pitch Pine-Scrub Oak Barren. Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society, 127(1), 19-32.

Kurczewski, F. E. (1999). Historic and Prehistoric Changes in the Rome, New York Pine Barrens. Northeastern Naturalist, 6(4), 327-340.

Latham, R. E. (2003). Shrubland longevity and rare plant species in the northeastern United States. Forest Ecology and Management, 185(1-2), 21-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1127(03)00244-5

Lesk, C., Coffel, E., D'Amato, A. W., Dodds, K., & Horton, R. (2017). Threats to North American forests from southern pine beetle with warming winters. Nature Climate Change, 7, 713-717. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3375

Liu, H. (n.d.). Southern Pine Beetle: Forest Insects& Diseases Fact Sheet. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Forestry, Division of Forest Health.

Motzkin, G., & Foster, D. R. (2002). Grasslands, heathlands and shrublands in coastal New England: Historical interpretations and approaches to conservation. Journal of Biogeography, 29(10-11), 1569-1590.

Ordnorff, S., & Patten, T. (Eds.). (2007). Management Guidelines for Barrens Communities in Pennsylvania (p. 208). The Nature Conservancy.

Cite as:

Braund, J., and E. Zimmerman. 2022. 2022. Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program. Dry Oak – Heath Woodland Factsheet. Available from: https://naturalheritage.state.pa.us/Community.aspx?=16093 Date Accessed: January 14, 2026