Dry Oak - Mixed Hardwood Forest

No Photos FoundSystem: Terrestrial

Subsystem: Forest

PA Ecological Group(s):

Central Appalachian – Northeast Oak Forest & Woodland

Global Rank:G4G5

![]() rank interpretation

rank interpretation

State Rank: S5

General Description

This type is widespread in Pennsylvania, occurring on dry, moderately acidic to somewhat calcareous soils derived from sedimentary rocks (siltstone, sandstone, shale). It is most often found on south and southwest-facing upper slopes. Common trees include white oak (Quercus alba), sweet birch (Betula lenta), shellbark hickory (Carya cordiformis), hackberry (Celtis occidentalis), red maple (Acer rubrum), sugar maple (A. saccharum), chestnut oak (Q. montana), black oak (Q. velutina), northern red oak (Q. rubra), pignut hickory (Carya glabra), shagbark hickory (C. ovata), white ash (Fraxinus americana), and basswood (Tilia americana). Conifers such as pitch pine (Pinus rigida), Virginia pine (P. virginiana), and eastern white pine (Pinus strobus) are also often among the list of canopy associates, but do not make up more than 25% of the overstory. Characteristic shrubs include flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), witch-hazel (Hamamelis virginiana), maple-leaved viburnum (Viburnum acerifolium), hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana), beaked hazelnut (Corylus cornuta), shadbush (Amelanchier arborea), and hop-hornbeam (Ostrya virginiana). Blueberry species, such as lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium pallidum) and deerberry (Vaccinium stamineum) are often present, but mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia) is uncommon. This type usually contains a somewhat richer herbaceous flora than the Dry Oak-Heath Forest (although still restricted by moisture availability). Herbaceous species include false Solomon's-seal (Smilacina racemosa), pussytoes (Antennaria plantaginifolia), wild-oats (Uvularia sessilifolia), Solomon's-seal (Polygonatum biflorum), ebony spleenwort (Asplenium platyneuron), poverty grass (Danthonia spicata), tick-trefoil (Desmodium spp.), rattlesnake weed (Hieracium venosum), wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis), Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica), a sedge (Carex communis), and whorled loosestrife (Lysimachia quadrifolia).

Rank Justification

This community is common, widespread, and abundant in Pennsylvania and in most Mid-Atlantic states. There are hundreds of occurrences of this type in Pennsylvania, across all regions based on plot data collected by PNHP. There are over 70 plots in the PNHP plots database occurring nearly all Level 3 EPA ecoregions of the state (67, 70, 62, 64, 69, 83). Maps of Pennsylvania State Forests and Game Lands include XXXXX acres of Dry Oak – Mixed Hardwood Forest, accounting for % of mapped forest acreage on lands managed by the two largest state land management agencies combined. However, this includes both the Dry Oak – Mixed Hardwood Forest and the Western Allegheny Mixed Oak Forest. Both are common.

The Dry Oak – Mixed Hardwood Forest is a broadly-defined oak-dominated forest type, which closely follows the NVC’s Northeastern and Central Appalachian oak-hickory forest communities at the Alliance-level (A4391, A4436, and 4437, USNVC 2019). Thus, the Dry Oak – Mixed Oak Forests can be further divided into three sub-types largely representing X largely regional varieties that follow regionally specific patterns in soils, elevation, and landform. The unifying vegetative characteristics of these types are the presence of hickory species and sugar maple and noticeable lack of a dense understory of ericaceous shrubs. All X finer units are considered Apparently Secure (G4) or Secure (G5) due to their wide distribution and large patch size.

Identification

- Occurrences are found on upper slopes and ridge-tops, often southern exposures.

- Dry moderately acidic to moderately calcareous soils.

- The shrub layer is not dominated by ericaceous (heath) species.

- Canopy dominated by upland oak species (chestnut oak, red oak, black oak, white oak, scarlet oak); conifer species comprise less than 25% of the canopy. Hickories (Carya spp.) and sugar maple (Acer saccharum) are common in the forest canopy.

- The canopy may be partially open, but the canopy closure should not fall below 40%.

Trees

- White oak (Quercus alba)

- Black birch (Betula lenta)

- Bitternut hickory (Carya cordiformis)

- Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis)

- Red maple (Acer rubrum)

- Sugar maple (Acer saccharum)

- Chestnut oak (Quercus pinus)

- Black oak (Quercus velutina)

- Northern red oak (Quercus rubra)

- Pignut hickory (Carya glabra)

- Shagbark hickory (Carya ovata)

- White ash (Fraxinus americana)

- Basswood (Tilia americana)

- Pitch pine (Pinus rigida)

- Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana)

- Eastern white pine (Pinus strobus)

Shrubs

- Flowering dogwood (Cornus florida)

- Witch-hazel (Hamamelis virginiana)

- Maple-leaved viburnum (Viburnum acerifolium)

- Hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana)

- Beaked hazelnut (Corylus cornuta)

- Shadbush (Amelanchier arborea)

- Hop-hornbeam (Ostrya virginiana)

- Lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium pallidum)

- Deerberry (Vaccinium stamineum)

Herbs

- False solomon's-seal (Maianthemum racemosum)

- Plantain-leaved pussytoe (Antennaria plantaginifolia)

- Bellwort (Uvularia sessilifolia)

- Solomon's-seal (Polygonatum biflorum var. biflorum)

- Ebony spleenwort (Asplenium platyneuron)

- Poverty-grass (Danthonia spicata)

- Tick-trefoil (Desmodium spp.)

- Rattlesnake-weed (Hieracium venosum)

- Wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis)

- Sedge (Carex pensylvanica)

- Sedge (Carex communis)

- Four-flowered loosestrife (Lysimachia quadriflora)

* limited to sites with higher soil calcium

Vascular plant nomenclature follows Rhoads and Block (2007). Bryophyte nomenclature follows Crum and Anderson (1981).

International Vegetation Classification Associations:

USNVC Crosswalk:

Central Appalachian Dry-mesic Oak – Hickory Forest (A4436)

Northeast Dry-mesic Oak – Hickory Forest (A4437)

Dry-mesic Oak - Hickory / Viburnum Forest (CEGL006336)

Oak - Hickory / Hophornbeam / Sedge Forest (CEGL006301)

Central Appalachian Acidic Oak - Hickory Forest (CEGL008515)

NatureServe Ecological Systems:

None

NatureServe Group Level:

Central Appalachian-Northeast Oak Forest & Woodland (G650)

Origin of Concept

Fike, J. 1999. Terrestrial and palustrine plant communities of Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Natural Diversity Inventory. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Recreation, Bureau of Forestry, Harrisburg, PA. 86 pp.

Fleming, G. P. 2006. Northern Piedmont Hardpan Basic Oak - Hickory Forest (CEGL6216). NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. (Accessed: February 4, 2022).

Fleming, G. P. and Coulling, P. P. 2010. Central Appalachian Acidic Oak - Hickory Forest (CEGL008515). NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. (Accessed: February 4, 2022).

Neid, S. L., Sneddon, L. A., and Gawler, S. C. 2012. Dry-mesic Oak - Hickory / Viburnum Forest (CEGL006336). NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. (Accessed: February 4, 2022).

Pennsylvania Community Code*

AD : Dry Oak – Mixed Hardwood Forest

*(DCNR 1999, Stone 2006)

Similar Ecological Communities

The Dry Oak – Heath Forest and Western Allegheny Plateau Mixed Oak – Hardwood Forest types are similar but occur on more acidic sites. The Dry Oak – Heath Forest often exhibits an overwhelming dominance of heaths in the shrub layer and the Western Allegheny Plateau Mixed Oak – Hardwood Forest type is limited to the Western Allegheny Plateau and Allegheny Mountains ecoregions. Hickories, along with sugar maple, are often more common in the canopy of Dry Oak – Mixed Hardwood Forest than in the Dry Oak – Heath Forest and Western Allegheny Plateau Mixed Oak Forest communities.

Yellow Oak – Redbud Forests are also similar to the Dry Oak – Mixed Hardwood Forests; however Yellow Oak – Redbud Forests will most often include a substantial number of species considered calciphiles in the understory

This type may share species and ecological site variables with the state’s mixed conifer – oak forests, Dry White Pine (Hemlock) – Oak Forests, Pitch Pine - Mixed Hardwood, Virginia Pine – Mixed Hardwood Forest, or Red Pine – Mixed Hardwood Forests. However, in these communities, specific conifer species make up over 25% of the canopy and subcanopy of the forest.

Fike Crosswalk

Dry Oak – Mixed Hardwood Forest

Conservation Value

Oak forests are both economically important and hold significant value for wildlife (Smith 2005, Martin 1961; TNC/PNHP 2015).

Threats

Threats to significant occurrences of Dry Oak – Mixed Hardwoods Forests include pests and pathogens, poor forest management, over-browsing from white-tailed deer, succession due to fire suppression, and fragmentation. Climate change will have profound effects on all ecological communities within Pennsylvania.

Dry Oak – Mixed Hardwood Forests have been greatly impacted by gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar) and the nature of outbreaks may result in catastrophic loss of forest canopy when combined with other ecological stressors over many successive years of large outbreaks (McManus et al. 1980). Areas heavily impacted by gypsy moth may first appear as woodlands on account of their open canopies and eventually toward red maple-dominated forests, especially in areas where heavy deer browsing has reduced the abundance of oak seedlings in the shrub and ground layers.

Development of natural gas and pipeline right-of-ways threaten the contiguousness of large unfragmented patches of this community and reduce the integrity of occurrences.

While invasive plants are uncommon within the interior of large occurrences of this community, forest edges will often harbor non-native exotic plant species such as multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), autumn-olive (Elaeagnus umbellata), and honeysuckle (Lonicera spp.). Japanese stilt-grass (Microstegium vimineum) may be abundant in the groundcover layer. Invasive plants are often an indicator of recent anthropogenic disturbance. Changes to natural hydrology and soil chemistry of these forests promotes invasive plants.

Management

Conservation and management efforts should focus on protecting large examples of this community type and ensuring regeneration. Activities geared towards limiting the spread of invasive plants, controlling deer populations and limiting the impact of browsing on tree regeneration, and promoting natural processes, like fire, will positively impact this forest community. Limiting fragmentation will ensure habitat requirements are maintained for forest interior wildlife species requiring large tracts of unbroken forest habitat.

Forestry activities should avoid older-growth stands. Managers should promote extended rotations and un-even-aged management within large patches of high-quality forests of this type. Lands surrounding rock outcrops and occurring between rock outcrops should be protected and managed as old growth to maintain corridors between them, facilitating movement of wildlife species.

Invasive plants found on the edges of Dry Oak – Mixed Hardwood Forest occurrences my find a way into the interior following development of trails, roads, and right-of-ways. Invasive plant control efforts should be focused on these fragmenting features and along forest edges. Drainage ditches and road culverts may alter natural site hydrology. Changes to natural hydrology and soil chemistry of these forests promote invasive plants.

Prescribed fire is a commonly applied managed practice in oak forests, especially Dry Oak – Mixed Hardwood Forests. Fire can be used responsibly as a tool for wildlife habitat management and forest management, and pre-and post-burn monitoring will help better understand forest community response to fire.

Over-browsing by high densities of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) can have a profound influence on regeneration of Dry Oak – Mixed Hardwood Forests. Shifts toward less-palatable species, such as red maple and sweet birch due to over-browsing, have been documented. Therefore, control of white-tailed deer is recommended as an important component of management of Dry Oak – Mixed Hardwood Forests.

Research Needs

Because communities are often the basic unit of mapping on public lands, and are utilized in predictions for rare species in Pennsylvania under different climate change scenarios, maintaining accurate, up-to-date maps of plant communities is important for conservation of rare species.

There is considerable variation among occurrences of the Dry Oak – Mixed Hardwood Forests with respect to canopy closure and the density of the understory shrub layer. Most Dry Oak – Mixed Hardwood Forests patches mapped on lands managed by the PA Bureau of Forestry and PA Game Commission are a mosaic of closed canopy forests and more open woodland area resulting from variation in edaphic variables and severity of past logging and disturbance events. More should be done to more precisely map these areas based on local variation in canopy and shrub density as this may impact the value to wildlife species, especially species relying on interior forest conditions.

This type is known from most regions of Pennsylvania. PNHP has quantitative data from only a very small number of sites in the High Allegheny plateau ecoregions, where it is represented by the finer natural communities associated with this region (NVC CEGL006301 and CEGL006336). Much of the work documenting matrix-forming communities like the Dry Oak – Heath Forest comes from National Park Service Vegetation Mapping efforts (Podniesinski et al. 2005, Perles et al. 2006b, 2006c, 2006d, 2006a, 2007b, 2007a, 2008). More field work should be conducted to document this community in the under-surveyed counties within this region – especially the northern tier counties in Pennsylvania.

Trends

The number and size of occurrences has declined due to development and logging. Many studies (Abrams and Ruffner 1995, Abrams 2000, Black et al. 2006, Johnson 2013, Abrams and Nowacki 2019) have used historical vegetation records to determine that oak-dominated forests were common prior to European settlement. However, we have limited historical data for the distribution for oak-dominated forests in Pennsylvania. Some authors have suggested that red oak and other species (see Abrams and Ruffner 1995) may be replacing historically dominant species, such as white oak, hickory, white pine and American chestnut in the absence of fire or other disturbance in certain ecoregions (Abrams and Ruffner 1995, Abrams 2000, Black et al. 2006, Johnson 2013, Abrams and Nowacki 2019)

Invasive plant species do not seem to be a major issue without significant disturbance to the canopy or soil. However, gypsy moth mortality and other canopy-altering disturbance events may enable invasive plants to thrive following establishment. Limestone gravel roads and trails and alterations to site hydrology my facilitate establishment of invasive plants such as Japanese stilt-grass (Microstegium vimineum) (Rauschert and Nord 2010, Nord and Mortensen 2010).

Development of natural gas and pipeline right-of-ways threaten the ecological integrity of large unfragmented patches of this community and reduce the size and contiguousness of occurrences.

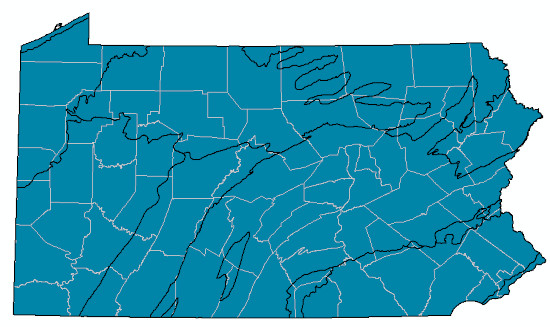

Range Map

Pennsylvania Range

This community occurs in all regions of Pennsylvania and is common, except for in the Western Allegheny Plateau and Glaciated Northwest (EPA Erie Drifts Ecoregion (61)) where it is limited to dry, south-facing ridge tops and represented by the NVC Association CEGL005023. It is much more common in the Ridge and Valley, High Allegheny Plateau, and Allegheny Mountains Regions where it is represented by the other four associations. The associations listed in the NVC are regional varieties, but represent oak-dominated communities with a significant understory of ericaceous shrub species, indicating dry, acidic soils.

Global Distribution

These forests are associated with the Central Appalachians, and generally follow the distribution of Braun’s Appalachian Oak Region (Braun 1950), with representative associations occurring from Virginia to Massachusetts.

Abrams, M. D. 2000. Fire and the ecological history of oak forests in the eastern United States. Page 46 Proceedings: Workshop on Fire, People, and the Central Hardwoods Landscape. USDA Forest Service Northeastern Research Station, Richmond, KY.

Abrams, M. D., and C. M. Ruffner. 1995. Physiographic analysis of witness-tree distribution (1765-1798) and present forest cover through north central Pennsylvania. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 25:659-668.

Abrams, M. D., and G. J. Nowacki. 2019. Global change impacts on forest and fire dynamics using paleoecology and tree census data for eastern North America. Annals of Forest Science 76:8.

Black, B. A., C. M. Ruffner, and M. D. Abrams. 2006. Native American influences on the forest composition of the Allegheny Plateau, northwest Pennsylvania. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 36:1266-1275.

Braun, E. L. 1950. Deciduous forests of eastern North America. Blakiston, the University of California.

Fike, J. 1999. Terrestrial and palustrine plant communities of Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Natural Diversity Inventory. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Recreation, Bureau of Forestry, Harrisburg, PA. 86 pp.

Fleming, G. P. 2006. Northern Piedmont Hardpan Basic Oak - Hickory Forest (CEGL6216). NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. (Accessed: February 4, 2022).

Fleming, G. P. and Coulling, P. P. 2010. Central Appalachian Acidic Oak - Hickory Forest (CEGL008515). NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. (Accessed: February 4, 2022).

Johnson, S. E. 2013. Native American land use legacies in the present day landscape of the Eastern United States. Ph.D. Dissertation. Pennsylvania State University.

McManus, M. N., N. Scheebergerm, R. Reardon, and G. Mason. 1980. Gypsy Moth. Forest Insect and Disease Leaflet 162. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Washington, D.C.

Neid, S. L., Sneddon, L. A., and Gawler, S. C. 2012. Dry-mesic Oak - Hickory / Viburnum Forest (CEGL006336). NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. (Accessed: February 4, 2022).

Nord, A., and D. Mortensen. 2010. Use of limestone gravel on forest roads increases abundance of Microstegium vimineum (Japanese stiltgrass).

Perles, S., G. S. Podniesinski, E. Eastman, L. A. Sneddon, and S. C. Gawler. 2007a. Classification and Mapping of Vegetation and Fire Fuel Models at Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area: Volumes 1 and 2. Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR—2007/076. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.Philadelphia, PA.

Perles, S., G. S. Podniesinski, E. Zimmerman, E. Eastman, and L. Sneddon. 2007b. Vegetation Classification and Mapping at Allegheny Portage Railroad National Historic Site [and associated files]. Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR—2006/079. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.Philadelphia, PA.

Perles, S., G. S. Podniesinski, E. Zimmerman, W. A. Millinor, and L. Sneddon. 2006b. Vegetation Classification and Mapping at Friendship Hill National Historic Site Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR--2006/041. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.Philadelphia, PA.

Perles, S., G. S. Podniesinski, E. Zimmerman, W. A. Millinor, and L. Sneddon. 2006c. Vegetation Classification and Mapping at Fort Necessity National Battlefield. Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR—2006/038. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.Philadelphia, PA.

Perles, S., G. S. Podniesinski, E. Zimmerman, W. A. Millinor, and L. Sneddon. 2006d. Vegetation Classification and Mapping at Johnstown Flood National Memorial. Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR—2006/034. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.Philadelphia, PA.

Perles, S., G. S. Podniesinski, W. A. Millinor, and L. A. Sneddon,. 2006a. Vegetation classification and mapping at Gettysburg National Military Park and Eisenhower National Historic Park. Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR--2006/058. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.Philadelphia, PA.

Perles, S., M. Furedi, B. Eichelberger, A. Feldman, G. J. Edinger, E. Eastman, and L. Sneddon. 2008. Vegetation Classification and Mapping at Upper Delaware Scenic and Recreational River. Natural Resource Technical Report. Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR—2008/133. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.Philadelphia, PA.

PGC-PFBC (Pennsylvania Game Commission and Pennsylvania Fish & Boat Commission). 2015. Pennsylvania Wildlife Action Plan 2015-2025. Pennsylvania Game Commission and Pennsylvania Fish & Boat Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Podniesinski, G., S. Perles, L. Sneddon, and W. A. Millinor. 2005. Vegetation Classification and Mapping of Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site. Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR—2005/012. Page 107. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Northeast Region. Philadelphia, PA.

Rauschert, E. S. J., and A. N. Nord. 2010. Japanese stiltgrass: an invasive on the move. The Ohio Woodland Journal 17:15-17.

USNVC. 2019. United States National Vegetation Classification Database, V2.03. Federal Geographic Data Committee, Vegetation Subcommittee, Washington DC.

Cite as:

Braund, J., E. Zimmerman, A. Hnatkovich, and J. McPherson. 2022. Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program. Dry Oak - Mixed Hardwood Forest Factsheet. Available from: https://naturalheritage.state.pa.us/Community.aspx?=16060 Date Accessed: March 31, 2025