Red Spruce Palustrine Forest

System: Palustrine

Subsystem: Forest

PA Ecological Group(s): Basin Wetland

Global Rank:G2?

![]() rank interpretation

rank interpretation

State Rank: S3

General Description

This type occurs on shallow organic soils or mineral soils with a substantial accumulation of organic matter. Red spruce (Picea rubens) is always present, usually dominant or codominant. Other tree species include eastern white pine (Pinus strobus), Eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis), tamarack (Larix laricina), red maple (Acer rubrum), gray birch (Betula populifolia), yellow birch (B. alleghaniensis), blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), and occasionally balsam fir (Abies balsamea). Rosebay (Rhododendron maximum) is common and often forms a dense understory. Other shrub species that may be present include witherod (Viburnum cassinoides), winterberry (Ilex verticillata), highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum), and mountain holly (Ilex mucronata). There is usually a pronounced hummock and hollow microtopography. Characteristic herbs occurring on hummocks include cinnamon fern (Osmunda cinnamomea), violets (Viola spp.), partridge-berry (Mitchella repens), Canada mayflower (Maianthemum canadense), goldthread (Coptis trifolia), dewdrop (Dalibarda repens), bunchberry (Cornus Canadensis), rough-leaved aster (Eurybia radula), Carex trisperma and other sedge species. The bryophyte layer is usually well developed on the hummocks and dominated by sphagnum while the pools are flooded or bare leaf and needle litter.

Rank Justification

Vulnerable in the nation or state due to a restricted range, relatively few populations (often 80 or fewer), recent and widespread declines, or other factors making it vulnerable to extirpation.

Identification

- Dominated by red spruce (Picea rubens), Eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis), eastern white pine (Pinus strobus), and tamarack (Larix laricina)

- Conifer tree species contribute over 75% of the canopy

- Hummock and hollow microtopography with sedges, forbs, and sphagnum and other mosses occupying the hummocks

- Canopy closure is greater than 60%

Trees

Shrubs

Herbs

* limited to sites with higher soil calcium

Vascular plant nomenclature follows Rhoads and Block (2007). Bryophyte nomenclature follows Crum and Anderson (1981).

International Vegetation Classification Associations:

USNVC Crosswalk:None

Representative Community Types:

Swamp Forest - Bog Complex (Spruce Type) (CEGL006277)

NatureServe Ecological Systems:

High Allegheny Wetland (CES202.069)

Southern and Central Appalachian Bog and Fen (CES202.300)

North-Central Appalachian Acidic Swamp (CES202.604)

NatureServe Group Level:

None

Origin of Concept

Fike, J. 1999. Terrestrial and palustrine plant communities of Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Natural Diversity Inventory. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Recreation, Bureau of Forestry, Harrisburg, PA. 86 pp.

Pennsylvania Community Code*

UK : Red Spruce Palustrine Forest

*(DCNR 1999, Stone 2006)

Similar Ecological Communities

Red Spruce Palustrine Forest and Red Spruce – Mixed Hardwood Palustrine Forest are similar in species composition and may be adjacent to each other. The main distinguishing feature is that Red Spruce Palustrine Forest has a canopy cover for conifers greater than 75% and Red Spruce – Mixed Hardwood Palustrine Forest has a canopy cover for conifers between 25% and 75%. They also tend to differ in the density and composition of the understory. The Red Spruce – Mixed Hardwood Palustrine Forest often exhibits a dense cover of shrubs while the Red Spruce Palustrine Forest usually has little shrub cover, but a dense carpet of sphagnum.

Red Spruce Palustrine Forest and Red Spruce – Mixed Hardwood Palustrine Woodland are also similar in species composition, but differ from each other in species dominance and canopy cover. Red Spruce Palustrine Forest has a canopy cover greater than 60% and composed primarily of conifer species, while Red Spruce Mixed Hardwood Palustrine Woodland has a mixed hardwood-conifer canopy cover equaling less than 60%.

Fike Crosswalk

Red Spruce Palustrine Forest

Conservation Value

This community serves as nesting habitat for songbirds such as blackburnian and black-throated green warblers and wintering habitat for many other songbirds. Rare plant species found in this community include creeping snowberry (Gaultheria hispidula), dwarf mistletoe (Arceuthobium pusillum), twinflower (Linnaea borealis), and rough-leaved aster (Eurybia radula), and rare animal species may include snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus). This community also serves as a buffer for sediment and pollution runoff from adjacent developed lands by slowing the flow of surficial water causing sediment to settle within this wetland.

Threats

Red Spruce Palustrine Forests are threatened by habitat alteration in the watersheds they occupy, nutrient input from surrounding uplands, and alterations to the hydrologic regime (beaver dams, road crossings that impede water movement, lowering or raising of water tables). Clearing and development of adjacent land can lead to an accumulation of run-off, pollution and sedimentation. Clearing adjacent lands can also lead to vulnerability of the community to wind damage since the trees have shallow root systems. As global climate change progresses, the range of this community type may recede north. Invasive exotic plant species are not likely to be a threat unless there is nutrient input from surrounding uplands. Spruce budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana) and exotic invasive insects that feed on conifers may be a threat.

In Pennsylvania, this community type is found in small watersheds on glacial deposits derived from sandstone and conglomerate. These wetland communities depend on low to moderate availability of nutrients, moderate surface water and ground water inputs, and probably cold temperatures. Development should be restricted to prevent alterations to the hydrologic and nutrient processes that drive this community.

Management

A natural buffer around the wetland should be maintained in order to minimize nutrient runoff, pollution, and sedimentation. Since these communities are impacted by nutrient inputs and wind throw, a buffer between any logging operations or development and the wetland is suggested. The potential for soil erosion based on soil texture, condition of the adjacent vegetation (mature forests vs. clearcuts), and the topography of the surrounding area (i.e., degree of slope) should be considered when establishing buffers. The buffer size should be increased if soils are erodible, adjacent vegetation has been logged, and the topography is steep as such factors could contribute to increased sedimentation and nutrient pollution. Direct impacts and habitat alteration in the wetland should be avoided (e.g., roads, trails, filling of wetlands). Where impacts are necessary low-impact alternatives (e.g., elevated footpaths, boardwalks, bridges that do not impede flow) are encouraged. Where disturbances are unavoidable, the wetland should be monitored for changes in vegetation, especially invasive species. Indirect impacts such as isolation of the wetland by development from other similar wetlands may be a threat to the persistence of the type.

Research Needs

It is possible that this and other conifer wetland types were never harvested at some locations. Knowing the ages of the trees and histories of the wetlands will provide some understanding of the natural successional trajectory of this wetland and the vegetation and landscape of Pennsylvania prior to large-scale development. With potential global climate change, this community type is likely to be significantly impacted. It should be monitored to determine impacts such as the health of species and shifts in species composition to determine if this community will persist in Pennsylvania.

Trends

Red Spruce Palustrine Forests were probably more common in the northeast at one time but declined due to wetland draining and filling. This type of alteration no longer occurs. However, the relative trend for this community is likely declining in the short term due to flooding from beaver activity. If natural succession is allowed to continue and potential climate change does not influence this community, many of these flooded occurrences will recover over time.

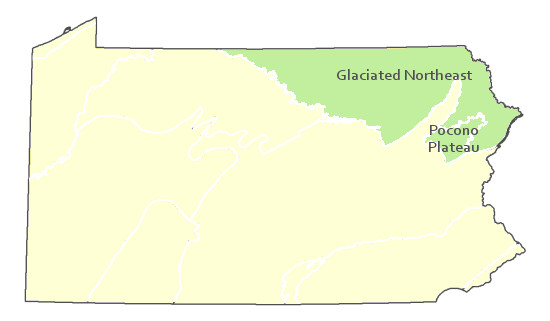

Range Map

Pennsylvania Range

Glaciated Northeast and Pocono Plateau

Global Distribution

Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania, Vermont, and West Virginia. It also extends into New Brunswick and Quebec in Canada,

Cowardin, L.M., V. Carter, F.C. Golet, and E.T. La Roe. 1979. Classification of wetlands and deepwater habitats of the United States. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Washington, D.C. 131 pp.

Edinger, G. J., D.J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero. 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Fike, J. 1999. Terrestrial and palustrine plant communities of Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Natural Diversity Inventory. Harrisburg, PA. 79 pp.

Larsen, J.A. 1982. Ecology of Northern Lowland Bogs and Conifer Forests. Academic Press, New York.

Merritt, J.F. 1987. Guide to the Mammals of Pennsylvania. University of Pittsburgh Press.

NatureServe. 2009. NatureServe Central Databases. Arlington, Virginia. USA.

Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR). 1999. Inventory Manual of Procedure. For the Fourth State Forest Management Plan. Pennsylvania Bureau of Forestry, Division of Forest Advisory Service. Harrisburg, PA. 51 ppg.

Rhoads, A.F. and T.A. Block. 2007. The Plants of Pennsylvania, 2nd ed. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Stone, B., D. Gustafson, and B. Jones. 2006 (revised). Manual of Procedure for State Game Land Cover Typing. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Game Commission, Bureau of Wildlife Habitat Management, Forest Inventory and Analysis Section, Forestry Division. Harrisburg, PA. 79 ppg.

Thompson, E. 1996. Natural communities of Vermont uplands and wetland. Nongame and Natural Heritage Program, Department of Fish and Wildlife in cooperation with The Nature Conservancy, Vermont chapter.

Wenger, S. 1999. A Review of the Scientific Literature on Riparian Buffer Width, Extent and Vegetation. Office of Public Outreach, Institute of Ecology, Univ. of Georgia, Athens.

Cite as:

Eichelberger, B. 2022. Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program. Red Spruce Palustrine Forest Factsheet. Available from: https://naturalheritage.state.pa.us/Community.aspx?=16031 Date Accessed: February 27, 2026